Camillo Catelli

1886 - 1978

by Paolo Ricci

The painter Camillo Catelli was born in Naples on August 18th, 1886, and died in 1978, at over ninety years of age. His life, at first glance, does not appear to offer great material for a fictionalized biography. He lived in the Carmine neighborhood, near the now-hidden Sebeto River. His house overlooked the old Villa della Marinella, and from its balconies, he could see the houses of the Maddalena district and the old Granili bridge, stretching from the port on one side to the Posillipo hill on the other.

From early childhood, Camillo Catelli drew and painted, though many of these early works are now lost, having been given to friends and relatives. When he began painting in earnest, his inspiration came from the landscape historically connected to the legend of Masaniello. At the same time, he envisioned a hopeful, industrious future for the city—an image of civic progress that he believed Naples should aspire to.

His activity as a painter dates back to 1908, when he first felt a strong calling to "pursue painting." His first true works from life were created during this time, painted from the balcony of his home overlooking the ancient Villa del Popolo—an old garden, now sadly destroyed. Beyond it, he could see the boats and large ferries entering and leaving the polluted port—a landscape full of life and work: dockworkers, fishermen, sailors, as well as everyday citizens strolling or resting in the shade of palm trees on the Villa’s benches.

The earliest known paintings, a few of which are still in the possession of his family, date back to 1913.

“During the war of 1915–18, I felt such a strong need to escape the sadness of the present that a deep desire to surrender myself to the joy of art grew within me—a love I had always felt since childhood. One day, I got up and, through the open shutters of my bedroom, I saw the beach in front of me bathed in sunlight, with a sailor in white walking across it.

After lunch, I put on my straw hat and, walking through Spaccanapoli, reached the old Giosi store, where I used to go as a boy to buy school supplies—pencils, rulers, and such. There, I gathered everything I needed to begin oil painting.

The next morning, I got up and, on a large piece of military canvas I had specially prepared, I painted the beach, the sea, the boats, and the sailor. I was fortunate: I painted well, and I liked the result.

That evening, when friends and relatives came to visit, they asked where I had gotten the painting from.

‘I bought it from a peddler,’ I replied.

‘Beautiful,’ they said, while I looked on, satisfied.

That was my debut as a painter. What you don't do, you don't know. And soon it was known that I was painting, and I had to produce several works for friends, relatives, and others who began requesting them.”¹

To understand Catelli’s artistic orientation at that time, it is important to note that he never imitated anyone literally. He remained faithful to this principle throughout his life. Even as his painting evolved, he developed a style and expressive power that, over time, placed him—naturally and contemporaneously—on the level of the great European artists who helped shape the creative spirit of the twentieth century.

A single episode from his youth is enough to reveal the aesthetic direction Catelli was already pursuing. He recalls:

“One day, as I was walking, weighed down by boredom, I found myself in front of a photographer’s shop window. There, I saw a small photograph, no larger than a business card, and I was enchanted by its composition. It was a reproduction of the famous painting The Brawl by Cammarano, which I had never seen before.”

This episode clearly illustrates his inner need to remain faithful to reality. It’s no coincidence that his first artistic awakening came from a painting—Cammarano’s—that was closest in spirit to Courbet’s realism.

Catelli’s work—whether from his youth, his mature years, or his final period—confirms the truth of Picasso’s observation:

“They speak of naturalism in opposition to modern painting. I would like to meet someone who has seen a natural work of art.

Nature and art, being completely different realities, cannot be the same thing. Through art we express our conception of what nature is not”.

In our view, Camillo Catelli’s art affirms the truth of Picasso’s insight about the relationship between nature and art. Art is, by its nature, an invention—a fantasy—but only when fantasy is understood as a way of questioning reality, a means of interpreting it, and ultimately transforming it into something new, it becomes a process of reconstruction: creating images that are not limited to evoking the surface—forms, shapes, and colours of reality—but that instead express the artist’s inner world—his emotions, his ideas, and his relationship, as a human being, with the history and culture of his time.

To quote Picasso once again: “To invent what nature is not.”

In this broader sense, all art of the past—from prehistoric cave paintings to Cubism and beyond—can be considered naturalistic. Not because it imitates nature literally, but because it reflects the human impulse to engage with, interpret, and give meaning to the world through creative expression.

The great art from the past remains alive and relevant today—timeless not by being detached from history, but because its creators managed to resolve the profound dialectical tension between human beings and nature. The man, not as an abstract being, a universal idea, but as a historical reality—rooted in time, culture, and circumstance. This art endures because it gives form to essential truths, not incidental details. It invents symbols and signs capable of expressing reality in its lasting, non-ephemeral essence, and translates these into a language that continues to resonate across generations.

From his earliest works, we sense in Catelli the presence of such signs—visual elements that go beyond mere observation. He translates what he sees into original forms that resist being reduced to fleeting or anecdotal truth. Within this framework, we can understand the "prehistory" of Catelli’s painting: these early works are naive in appearance, yet they already display a nascent power to transform perception. Through deliberate distortion of form, Catelli begins to express not just what he sees, but what that reality means—rendering it emblematic.

In the small landscape paintings preserved from the early 20th century, there is a dreamlike, fairytale vision of reality. This imaginative perspective foreshadows—and in some ways parallels—the work of Alberto Savinio and his unique brand of "domestic surrealism," where everyday scenes are charged with poetic and metaphysical overtones.

In his small-scale portraits, distortion often serves a more unsettling purpose. With almost irreverent force, Catelli reveals the inner character of his subjects, exposing psychological truths that lie beneath the surface. These works confront us with the hidden nature of individuals, not through idealization but through a raw, often jarring honesty.

Among the paintings from these early years, one canvas stands out as an authentic masterpiece of Neapolitan art from that era: the portrait of the artist’s wife, painted around 1918. It presents a profile both pure and powerful, evoking the serene geometry of Piero della Francesca. And yet, the atmosphere it breathes belongs to another world—a modern one—resonating with the same spirit that animates the neoclassical works of Picasso during his return to order. It is a portrait suspended between tradition and modernity, reverence and innovation—a testament to Catelli’s emerging voice in a century torn between memory and transformation.

This approach alone would be enough to lend prestige and authority to any artist capable of conceiving an image that fully expresses tenderness and profound love for a woman—feelings held within, expressed through a form that avoids sentimentality or easy emotion. The tone of the portrait is orchestrated in two subdued hues, and the painting is both intense and composed. It centers above all on the woman’s gaze, and on her hair, shaped like a helmet, recalling the feminine figures of the Tuscan Quattrocento.

So far, we have explored the first steps, the early experiences of Camillo Catelli—a period that came to a close around 1929, marked and interrupted by events that left lasting imprints on the artist’s life, at times painful, at times fruitful and joyful. At this point, it may be helpful to briefly turn to his biography.

The first formative event in Catelli’s life occurred during his childhood, when his father—after returning from a trip to Egypt—disappeared without a trace. There was never any further news of him. Catelli rarely spoke of this. An only child, he was raised by his grandfather.

“By family tradition I should have become a doctor (...), but I was enrolled in technical schools (...).

From my grandfather, a hatmaker—as they used to say—I could learn nothing,”

he once said, adding that his grandfather had already left the trade by the time he was a child. It was then that the sense of discomfort, of disorientation, began to set in.

“I asked myself: why must I live one trouble after another?”

And then, the war broke out.

In his autobiographical writings, Catelli admits to his shyness and to a lifelong tendency toward solitude.

“This desire to hide myself was explained to me, much later, by a friend—a university professor—who understood that this inner struggle was the result of a character naturally inclined to melancholy (...). I never wanted to draw attention to myself, and even less did I want to be the subject of scandal.

I didn’t want to appear immoral or like a womaniser—because I wasn’t. I never sought the spotlight, nor was I vain like so many so-called Casanovas.

If anything, it was the women who wanted to conquer me—not the other way around.”

And yet, the great love of his life came unexpectedly. In recalling that moment, Catelli offers us not only an intimate glimpse into his heart but a vivid portrait of the place where that encounter occurred:

“At the far end of Corso Garibaldi, near the Porta Piccola of the Carmine, a strong wind was blowing.

In a summer tram car, the curtains fluttering to shield the passengers from the sun and wind, I saw a girl—my uncle’s wife’s sister.

The wind was strong. I quickly said goodbye to a friend and went home, hoping to meet the two women who would be there.

I don’t know if she had a fondness for me—maybe she did, judging by her sweet words and flattery when I later visited her in Capodimonte, where she lived.

One day, we were alone in my aunt’s bedroom. We spoke of our love. It was our first love—a pure love, untouched even by a single kiss (...).

We were only sixteen. I remember one evening we visited an aunt who lived in a beautiful building in Sant’Eframo Vecchio.

On the way back it was raining, and we walked together under the same umbrella.

The fine rain seemed to rock us gently. I wished the road would stretch on forever—that it would never end.”

The girl’s name was Virginia Russo. In 1916, in the middle of the war, Catelli married her.

That same war, however, filled him with revulsion. He could neither understand nor accept its cold, inhuman logic.

“To have to kill one’s fellow men at all costs—it’s intolerable,” he said.

“The more corpses you produce, the greater you’re considered. But behind every man you kill is a crowd of faces: children, siblings, parents who tremble for him.

War is tragic for everyone, but for some it’s an unbearable torment—it is a threat to life itself, to culture, to prosperity.

Nothing in life is truly certain, but nothing is more precious than life.”

After the war, Catelli switched to the industrial career and, for a time, achieved a modest level of financial security. Yet this life brought him no real satisfaction. His mind was not suited to managing accounts or pursuing profit. Instead, it was attuned to culture, to curiosity, to the study of animals, and to an intimate awareness of the rhythms of the seasons.

With the rise of fascism, he immediately grasped the threat that dictatorship was posing to the Italian people. His industrial activity—with all its ups and downs—was one of the first casualties of the new political order. Still, he carried on until 1929, when Mussolini’s decision to fix the lira’s exchange rate at 92.46 to the British pound triggered a collapse in many sectors of the Italian economy. The consequences were swift and devastating: Catelli found himself impoverished almost overnight, forced to radically alter the course of his life.

He and his young wife were confronted with a definitive and dramatic choice—a choice that meant relinquishing everything they had achieved in civil society, in human relationships, and in cultural habits. Catelli decided to retreat from the city and settle on the Camaldoli hill, where he owned a plot of farmland and a farmhouse. There, with his family, he resolved to become a farmer, throwing himself into an unfamiliar world with rhythms and demands he barely understood.

He committed himself to the land, working it with his own hands, alongside his very young children, who were too small to offer much help in what was a hard and unrelenting task. Camaldoli was isolated and remote—at the time, in 1930, it was virtually inaccessible. One could only reach it on horseback or by mule, along narrow, steep, shadowy paths.

What sustained him was his extraordinary love for animals—a love that never waned, even in old age. He could often be seen in the meadows, among the greenery, particularly near two twisted-trunk mimosa trees where pigeons gathered by the hundreds and would fly to him as he approached. He often said:

“He who does not love animals does not love humankind.”

The first challenge in adapting to this new life was learning the “vocabulary of nature,” which he gradually deciphered through his passion for open spaces and the freedom he cultivated for himself and for all living beings around him. The isolation was nearly absolute for someone like him, born and raised in the city. You could count the houses on Camaldoli hill on one hand. The road that led there was rough and unpaved, and in late autumn, it was blanketed in fallen leaves that made a croaking, almost human sound when carts rolled over them. When it rained, water surged down the path’s sides like a torrent, sweeping away anything in its way.

Soon, the local peasants became his friends. Many were illiterate and turned to him not only for help in writing letters but also for advice—trusting in his wisdom, his education, and his quiet dignity.

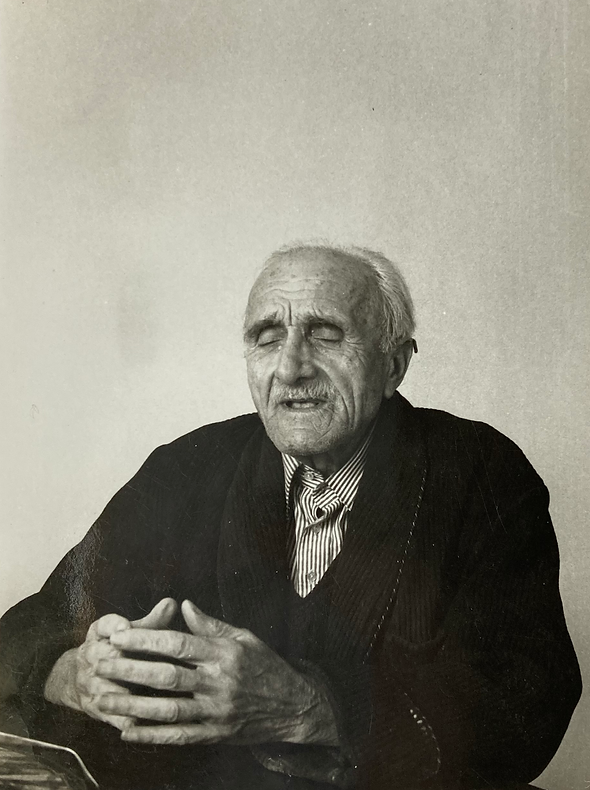

Through working the land, Catelli underwent a profound transformation—one that was as physical as it was spiritual. Over time, his features hardened. Deep wrinkles carved themselves into his face, and his hands grew rough, bony, and calloused. It was a path of survival. Emerging from the crisis that had upended his life, Catelli threw himself into agriculture with unwavering resolve. He knew that the only way forward was to make the land yield, and he pursued that goal with clarity and determination.

From dawn until dusk, Catelli devoted himself entirely to the labor of the fields. In the evenings, exhausted, he found solace in imagination and in the few cherished books he had managed to save from the collapse of his former life: The Treatise on Painting by Leonardo da Vinci, The Betrothed by Manzoni, and The House by the Medlar Tree (I Malavoglia) by Verga.

But the most painful sacrifice for Catelli was painting—an art he was forced to abandon from the very first day of his new life in the countryside. After working the land from sunrise to nightfall, and once the tools had been set aside and the animals cared for, he allowed himself the quiet refuge of reflection. He would write down thoughts and observations born of his new experience—sometimes moral, often philosophical. What became a true lifeline for him, however, was a near-daily practice of writing a sort of personal diary. In its pages, he recorded reflections on life, notes on agricultural labor, and above all, deeply considered thoughts on painting and the arts in general. This was his only way to remain intellectually connected to art, to soothe the ache of nostalgia and to nurture the still-burning, though hidden, passion for painting.

Catelli hoped that once his children were old enough to contribute meaningfully to the work of the farm, he would be able to return to art with renewed energy and purpose. But more years passed. The rise of fascism and the Second World War brought fresh challenges and suffering.

His children were drafted into the military; three of them were captured and endured the horrors of Nazi concentration camps, from which they were eventually liberated by the Soviet army. In 1945, with the long-awaited return of his sons, the family was whole once again, and for the first time in many years, there was hope for the future.

With four capable young men to help work the land, Catelli was finally free to dedicate himself once more to painting and sculpture. In fact, a few years earlier, around 1940, he had already found a way to return to drawing. His subjects were drawn from the life around him—intimate scenes and familiar faces: portraits of the women in his household, especially his daughters, beloved images of girls at rest or work, women doing laundry, sewing, or a child asleep in the sunlight. He sketched agricultural tools, farmyard animals, horses, oxen—anything that captured his imagination.

Each drawing was signed and dated, and many were labeled sketch, perhaps to indicate their didactic or exploratory nature. Around 1944, this vast collection of drawings could be found scattered across the floor of the small study where Catelli spent his quiet hours. From even a cursory examination of their style, it was clear that these works marked the beginning of a significant artistic evolution.

These were sensitive yet powerful drawings—executed with energy, precision, and a clarity of intent. The form was both expressed and suggested through lines that were constantly reinvented: bold, expressive, synthetic. One could see in the composition, in the arrangement of figures, and in the expressive distortions a vision of the stylistic direction Catelli would take—a direction marked by originality and genuine sculptural force.

By 1944, Catelli began to paint again, producing portraits of extraordinary emotional and expressive intensity—including those of his mother and a series of tormented self-portraits. In these works, one already sees his stylistic independence and his break from traditional tonal conventions. His art had taken on a clearly Expressionist tone.

A painting such as Sleeping Mother, with her head resting gently on one hand, speaks not only to the Neapolitan tradition but evokes the works of artists like Ottone Rosai and Constant Permeke—figures who, like Catelli, explored the profound dignity of the human form through expressive distortion and emotional weight.

But with the return of his children, as already noted, the artist broadened and deepened the themes of his painting. He looked around himself with renewed wonder, painting everything as if discovering it for the very first time. Trees, meadows, skies, and the farmhouses drew his attention—especially for the intense harmony that radiated from their spontaneous yet refined architecture.

He rendered, with a kind of trembling reverence, the beauty of these elemental forms. In the dead of winter, for example, he captured the solemn mood of leafless trees and snow-covered fields. As he traced the compositional force-lines of these scenes, he began to uncover the abstract beauty within them.

From these early works already emerged the most defining quality of Catelli’s mature painting: a kind of harsh, monumental power. But this was not a monumentality that was still, cold, or cerebral. It was full of life—of blood and human warmth—expressed through fragmented forms and a bold, unapologetic vision. His art sought the essential, avoiding incidental detail or picturesque flourishes.

Colour reigned supreme in these works. Rather than describe, it defined—applied in expressive, meaningful patches that built bodies and landscapes through solid, interlocking planes. These planes intersected with an internal logic, evoking a compositional harmony reminiscent of Cubism. Catelli’s painting of the 1950s is, therefore, at once raw and sophisticated—harsh, concrete, and deeply realistic. It was a form of realism that perfectly aligned with his character: a man shaped by intense and painful experiences, who now looked out at the world with calm detachment, focused solely on the most essential and enduring aspects of human feeling.

“All theories that go against human nature are impossible to apply,” he wrote in one of his journals. His creative research aimed to return to the sources of nature, resisting the distortions of modern media and superficial novelty. Reading the classics helped guide him: alongside Leonardo, Manzoni, and Verga, he had grown especially passionate about Leopardi. He read the Homeric poems regularly. Speaking of Leonardo da Vinci’s Treatise on Painting, Catelli claimed it contained the most extraordinary descriptions of battles in all of literature. “I never had a teacher,” he also said, “but I studied the greatest master and art historian: Vasari.”

According to Catelli, the visual arts are uniquely able to tell the story of humanity “from the inside.” A striking note from one of his journals reads:

“The human mind is not yet capable of writing the history of life in such a way that it would also be the truest history—one in which we could actually live, rather than simply recount the cases of historical figures, often unknown even in their own times and places. To truly understand the historical climate in which people once lived, we would need the testimony of the visual arts—on par with literature and historiography. Only then would the things, the facts, the events, and the passions of those people be not just true, but beautiful.”

Now, at last, Catelli could fully dedicate himself to art—painting, drawing, sculpture. And his creativity exploded with unstoppable force. He painted every day, sometimes even twice a day. The canvases accumulated rapidly, stacked on the floor, in piles on furniture, and even resting on barrels.

Catelli saw very few people. He kept in touch mostly with old friends from his youth or with a small circle of people that lived on Camaldoli—among them, a doctor, a literature professor, and a few other "intellectuals." Occasionally, around 1950, he welcomed festively visits from notable artists such as sculptor Giovanni Tizzano, painter Emilio Notte, Francesco Galante, Franco Girosi, and sculptor Saverio Gatto. But these visits were infrequent. In effect, Catelli’s painting remained virtually unknown to the wider public.

Then, in 1956, a Neapolitan gallery organized an exhibition of the painter from Camaldoli—and for some of us, it was a thrilling discovery. I wrote extensively about it at the time, celebrating the emergence of an artist who, I believed, enriched the field beyond the realm of amateurism. I compared Catelli’s work to that of Luigi De Angelis for its honest, healthy, and direct visual impact.

His imagination, I noted, was not stifled by literary or religious fears or superstitions. Catelli was a secular, free-spirited, and clear-eyed painter. His works showed a sense of order and proportion, constantly interpreting reality with a focus on the human element. His style struck me for it being solid and deliberate—clearly the expression of someone who wanted to convey precisely what he felt, in a language that was never haphazard but always rigorous, continuously regulating its expressive force.

“There is something solemn, even noble,” I wrote, “in the light that suffuses his Camaldolese landscapes. And in the dry, exact modelling of his portraits, there shines a great light of humanity.” I continued: “If I were to draw comparisons or define his artistic lineage, I wouldn’t know where to begin. I’ve already mentioned the noble, classical character of his painting, but there is also something wholly contemporary and modern in the feeling that permeates his work.”

Perhaps the most appropriate point of reference is Rosai—especially for that sense of resigned monumentality, of intimacy shaped into symbol. I cited several of the works on display at the time, including Work in the Fields, Autumn, Sunset, and The Hermitage of Camaldoli, and I concluded with this remark: “I’ve mentioned Rosai, but I would add another Tuscan name: Lorenzo Viani. I do so to highlight what I see as Catelli’s most authentic qualities—his toughness and Italian candor, and the reminiscence of a frankness, typical of the Viareggio painters from the 15th-century.”

The essence of my review was summed up in one sentence:

“Whoever presents themselves in the world of art with these characteristics is no longer—indeed, could never be—just a primitive or a naïve: he is an artist, a painter, full stop.”

That Catelli was, at least for some of us, a great painter is beyond question—he remained so until his death, an inventor of brilliant rhythms and forms.

In an autobiographical piece, he stated, after all, that an artist draws strength from a force that is uniquely his own, not that of another.

This means that genius—the power to express oneself through painting or other plastic arts—is an unrepeatable and personal quality, attributable only to one’s own life experience and culture.

It may seem, and to some extent it is, a self-evident truth;

Rather, it asserts a truth that many artists—and critics themselves—often ignore or forget, while chasing the phantom of a codified, generalized, and sponsored language: that is, a tendency toward an absurd and abstract unity of style that conceals the anxiety of keeping up with fashion and the rapid shifts in taste dictated by the art market and other mass media instruments.

Within his solid human and moral framework, Catelli aimed at a continuous verification of the truth and necessity of his art, in relation both to the visible world and to the inner world of his affections and his simple conception of life. This vision had gradually formed in him through his constant connection with the harmonious and stable natural world and its laws, and through his passionate and mindful work as a farmer, a man of the land, deeply familiar with the laws that govern plant life, the cycles of the seasons, and the mysterious resonance between the events of the cosmos and the cycle of plant production.

"I observed the world in which, like everyone else, I have lived," the painter further affirms—as if to underline the contemporaneity of his art, that strange and seemingly inexplicable fact of the autonomous, independent development of his language and of the original expressions Catelli achieved—and always had achieved—at the very same time as the discoveries of the European avant-garde.

A mediated contemporaneity, born from a profound and human sense of reality, that is translated into solid, definitive images that belong to (and are of) our civilization, yet seem to pre-exist it—with that remote and, at the same time, vibrant beauty that only an intimate communion with nature can grant an artist.

And it is through that constant and passionate dialogue that Catelli attains expressive freedom and happiness—always varied, and always his own.

Guttuso recalls that during a visit to Picasso in 1949, a young painter asked the master whether, after centuries of figurative art, it was still worthwhile to depict anthropomorphic forms.

Picasso replied: “I’ve always known that you make wine from grapes—it’s never happened the other way around.”

The apparent good-naturedness of Picasso’s reply to his young friend, it seems to me, clarifies many things regarding the problems of modern art. First, it dismantles the myth of so-called artistic autonomy; second, it brings the question back to the proper terms in which it should be posed, to avoid falling—as so often happens today and in the past—into abstraction and arbitrariness. These are, in fact, the terms tied to the human, social, and cultural factors of our time, without consideration of which any artistic creation loses its necessity and poetic truth.

The passionate insistence with which Catelli scrutinises the faces of his family members, or the intimate corners of the Phlegraean and Campanian landscapes—both closely connected to his personal and artistic history—allows him to capture expressions, moments, and atmospheres that render the vast repertoire of his images rich in variety and ever-renewed. These images gain plastic rigor and value through a continuous invention of forms: discovered and rendered figuratively because, in every subject—human figure, tree, landscape, flower, horse, etc.—the artist captures, beyond appearances, their atmospheres and secret rhythms, their unique architecture; in short, those mysterious and internal aspects of reality that allow him to create a physiognomic or landscape characterization that has nothing to do with petit-bourgeois verisimilitude.

His paintings are never “charming,” but instead have the austerity and ancient synthesis of the remotest Italic figurations—a classicism that, interestingly, encounters the broken, “battered” language of the first great Cubists (especially Picasso), and, from a colouristic perspective, the Fauves.

Colour, in Catelli’s painting, is effective insofar as—as Picasso claimed—“it represents one of the constructive elements of volume.”

From this arises the extraordinary stylistic unity of his works and the coherence of the linguistic process through which the artist achieves the synthesis between colour and drawing, creating true images that nonetheless spring from imagination and invention.

Catelli, in terms of his cultural background, way of life, and family traditions, is a man of the nineteenth century. He knows it and says so—indeed, he emphasizes it with pride. And yet, his art has nothing that could, even indirectly, be linked to the taste of that century or to the tonal painting—however illustrious—that found its highest expression in Naples (think of Gigante, Mancini, Cammarano, Migliaro). His painting is therefore entirely physical, entirely animal, if these words can suggest something profoundly earthly and natural. It is a kind of painting in which, as with the Fauves, colour reigns supreme—exalted in its pure and absolute chromatic values, excluding blending and half-tones.

The modernity of Catelli’s artistic language, in addition to his “wild” use of colour, also stems from another element typical of avant-garde research—from the Impressionists to all contemporary art: the tendency toward deformation, through which the artist breaks down the forms of visible reality in order to recompose them in a different order. This reordering highlights their atypical character and allows for a reading freed from journalistic or illustrative temporariness, aiming instead at the universal value of the image—an aspect that is itself a form of classicism.

In this sense, certain works by Catelli evoke the ancient figurations of the Apulian-Lucanian tradition, which the artist seems to draw from spontaneously and naturally, in a way similar to Picasso, when he seems to draw from the archaic forms of art from the Rhône basin or African tribal imagery.

At the beginning of this discussion on Catelli, it was said that his painting retraces, almost automatically (and mysteriously), the entire path of contemporary art. It must be clarified, however, that the encounters, the extraordinary stylistic and linguistic coincidences between his works and those of the most prominent figures in European art, are entirely accidental. They occur because of an identical starting position of the artist in relation to visible reality.

The great lesson of the historical avant-garde lies in the achievement of extraordinary expressive freedom—a kind of innocence that the pioneers of artistic renewal reached through a rich and deep cultural experience and an intimate adherence to the ideas and ways of life of our time.

We know very well how these achievements retained their revolutionary energy and poetic richness—until the moment they became formalized in an academic sense, transforming into a refined language for the initiated.

But the great “Negro” Picasso of Les Demoiselles d'Avignon and his other pre-Cubist masterpieces; the Matisse of the famous Portrait with a Green Stripe and his other magnificent and robust paintings created between 1906 and 1910; the early masters of Expressionism—Kirchner, Nolde, Schmidt-Rottluff, Pechstein, Kokoschka, the young Van Dongen, the Russians Konchalovsky and Malevich, the Austrian Schiele, the Belgian Permeke, the French artists Derain and Braque in their Fauvist period—before their works underwent the process of commodification, all preserved their aggressive charge and a popular content.

To that critical and cultural climate the entire body of work of Camillo Catelli must be connected. The fact that, by instinct and in a completely natural way, this great peasant painter independently traveled the same path—developing a language invented on his own but parallel to that of the historical avant-garde masters—does not diminish the originality and inventiveness of his painting. On the contrary, his work, as I’ve said, is unrelated to the Neapolitan tradition of the past two centuries and instead arises spontaneously from the same ideal positions that motivated the pioneers of modern art, thus effectively placing him within the same stream of artistic research and leading him to the same stylistic and linguistic achievements.

He is, however, distinctly characterized by his strong, raw, and primitive sense of form, as well as by his loyalty to themes directly tied to the land, to the countryside, and to those who live and work there.

He always insisted that he had never modeled himself after any modern or ancient artist. By this, he clarified, he didn’t mean he hadn’t admired the old masters. “One day, at the Naples Museum, due to certain strange effects of light, I mistook figures in a Parmigianino painting for real flesh-and-blood people. Any book that had to do with painting was something I longed to read. As a boy, I visited museums and exhibitions, but I never followed fashions or trends. I remained faithful to my principles and never thought of profiting from what, for me, was—and remains—a pastime.”

For Catelli, then, painting was pure enjoyment. And when, due to the weight of age, he decided to stop working the land, this pastime occupied him continuously throughout the day, even late into the evening.

He would paint three or four canvases or sketches a day, even if not all were completed. Often his favorite models—his grandchildren and great-grandchildren, forming the large and lively Catelli clan—would quickly grow restless with the stillness their grandfather demanded and would abandon their “poses” to return to their favorite games. Catelli would pretend to get angry and chase after them for a bit, then move on to something else—perhaps painting a rose or the view of the countryside framed by a window. When he later picked up the unfinished paintings to complete them, his inspiration was always fresh, the emotion vivid and pulsing.

He worked calmly, donning his thick glasses, like a craftsman intent on building an object. His small palette, resting on a chair, was always within reach. He would squeeze out only a small amount of paint, and it was marvelous to watch how the image gradually took shape on the canvas or cardboard—following a process of successive synthesis that, beginning with the most attentive and meticulous observation of reality (Catelli would often even use a measuring tape to measure the features of a face), would lead to the definition of an image richly coloured, yet preserving the inner essence of the real—an essence he wanted to be and appear truer than the truth.

From 1944—the year in which his continuous painting activity began—until the final years of his life in 1978, Camillo Catelli’s painting developed with remarkable consistency and continuity, always aiming toward a synthesis of colour and form, and evolving, always unexpectedly, through classical figurative solutions that were concrete and essential.

As for his "prehistory," referring to the period that ended around 1930, when Catelli painted as an “amateur,” as we’ve already mentioned, traces of it remain in his later production. This demonstrates not only the thematic coherence of his work but also the constancy of his “natural” inspiration. The portrait of his wife from 1920 remains a key reference point, particularly for its classicist and Picassoesque resolution—a solution that reemerges and deepens in the paintings from his return to painting in 1944. From that point and through the early 1960s, the theme of the human face—especially of women and children—is marked by a volumetric rigor that we might refer to, for simplicity’s sake, as “Picassian.”

In the paintings Figure in the Countryside (1956) and Woman Reading (1957), the inspiration appears to draw not only from the volumetric and monumental power of the figures but also from a kind of Courbet-like naturalism, as well as Impressionism—especially in the Cézanne-like architecture of the trees.

It’s perhaps useful to insist on the artist’s perfect innocence, spontaneity, and innate instinct, which led him to achieve a painting style that is both highly refined and “cultured.” It’s also necessary to point out that, from the moment he discovered his vocation, the artist always relied on an instinctive illumination that guided him—and always would guide him—to conceive images that seem inspired by masters of modern painting whom he had never known. This is all the more remarkable considering that the artist had never even seen the works of those painters—whether in person or through reproductions—to whom one often feels compelled to compare Camillo Catelli upon viewing his work.

The phase of Expressionist deformation was still ahead, but one can already sense its direction in certain emphatic or vigorous accents—signs of his art’s developing tendency toward an expressionistic and biting edge. This is evident in numerous paintings depicting variously posed figures: young people sitting or studying, lying on a lawn or a sofa, or leaning out of a window framed by lush vegetation reminiscent of the backgrounds in Kandinsky’s more “musical” works. At times, the construction of the figures recalls Malevich’s “peasant” period, especially in the way the human form is reduced to essential geometric shapes. In some portraits, the deliberate lack of grace reaches a striking intensity, resembling certain primitive artworks: such as the head of a young man with long, wild hair—an image both modern and emblematic of urban youth—or the tormented and dramatic portrait of Rita, a beautiful young woman whom the painter sees and transforms into a kind of sorrowful existential mask.

For Camillo Catelli, a landscape, an aspect of nature—a peach tree, an apple tree, a chestnut tree, the sun’s reflections through a tangle of branches, the colour of the earth, of the underbrush grasses, even the trace left by a farm cart or by a farmer’s feet—constitutes an intimate part of a reality that he understands deeply and inwardly. The constituent elements of a landscape are, for him, a matter of connection, in the same way he interprets a human gaze, a smile, an expression of pain or joy. Catelli never has an objective stance—he is always involved, often overwhelmed, in front of the spectacle of nature. For this reason, his paintings inspired by natural scenes or the hours of the day bear clear signs of the emotion and affective participation of someone who follows the generative process as it evolves. Thus, his landscapes are somewhat like the harmonic development of a highly passionate, if sometimes elusive, theme.

In his paintings, what stands out is the annotation of a specific hour or an unexpected effect, following the intuition of a mood. The true protagonist is always the emotional state—the intuition of a rhythm and a form that strikes like an unforeseen element. From this arises the ever-varied and original atmospheres that translate, in plastic terms, into the emphasis on a particular aspect of the scene that inspires the artist. The countryside of Camaldoli thus rises to the level of a perennial symbol within the unfolding of his rustic poem, which is rooted in ancient culture while at the same time being entirely contemporary. For example, in certain winter landscapes, the structural lines—the architecture of the painting—correspond to visible reality, but they intertwine and blend into something different, based on colour and an image partly removed from that objective reality.

colour dominates in Catelli’s landscape painting; it determines the forms of objects: the trees, the rocks, the earth. colour, as a living thing, creates a kind of pantheistic atmosphere; the spatial planes of the composition are those the artist intuits through colour; the shadows are coloured just like all the other natural elements. In this sense, Catelli’s painting instinctively recreates the fauve language of Matisse, Braque, Marquet, and Vlaminck.

Catelli’s landscape themes are varied—often infused with sensations or even premonitions of a different reality, such as that of the city. Symptomatic in this regard are the paintings in which, in the distance, the outlines of urban buildings appear, or Mount Vesuvius—a mountain that, like in certain paintings by Gigante inspired by Naples, is seen in its gentler, more inviting guise.

For many years, Catelli painted the Camaldoli area—the vegetation, courtyards, and roads of the hillside. But at a certain point, after 1960, when his children convinced him to spend a few months by the sea, the artist found himself confronted with a new theme, a different reality—open and clear horizons, uniform beaches, and distant mountains mirrored in the sea. Faced with such a different subject, Catelli immediately found the key to interpreting the horizontality of that other nature. He thus arrived at synthesis by stripping the image down to the essential, reducing it to the simplicity of planes and marks, so that certain views of Minturno recall the Lagoon paintings of Virgilio Guidi.

Still life is a theme that fits fully within Catelli’s total artistic commitment. For him, painting flowers or fruit means engaging just as completely, with the same seriousness and significance, as when painting a figure, a face, or a landscape.

In painting expressive subjects, Catelli shows the same dedication as he does for any other theme; there is no prejudice towards any "genre" in him, but everything contributes to defining a state of mind.

The numerous paintings of "roses" present, for Catelli, expressive challenges of every kind that a painter faces. He does not simply continue the representation of iconographic facts; instead, he uses colour and form independently of those facts. The construction of still lifes cannot, therefore, disregard the environmental context and the construction of the architecture, of the thing itself. The petals of the roses have the "living" intensity of any element of figuration, be it human or landscape. A painting from 1974 entitled "Roses" is exemplary as a compositional value; the theme of transforming a rose into something that is both a flower and a fruit elevates to the complexity of a more intricate compositional motif, where formal synthesis and expressive deformation are predominant. In cases where the composition is more articulated, the stylistic value of the painting becomes even more evident. For example, in a still life from 1964, the motifs are varied: the plate, the fruits, the fish—all set against a Camaldoli landscape. But where he achieves a particularly successful synthesis is in the painting titled "Interior-Exterior," with the magical atmosphere of a reality seen in a dream. In general, Catelli’s still lifes always have this ambivalent nature. The most appropriate reference to identify the reason for their great appeal is the memory of the great fauve painting, especially that of Matisse.

Catelli painted his numerous grandchildren in all hours of the day, in the sunlight and indoors. His favorite was Matelda (Matildella), as he called her. The beautiful girl submitted to all the painter's demands, being painted in the strangest poses—posed, sleeping, or reading a book; on the terrace or in the countryside. Catelli’s extreme freedom in interpreting Matildella's figure, in all poses, whether natural or constrained by the painter's demands, reached its peak in the deformation and overwhelming of anatomical facts and even the physiognomic character. There was in him a need for extreme expressive freedom that transformed into surreal fantasy.

For example, many portraits of Matildella, even when so deformed or even monstrous, are nevertheless strikingly similar. Yet, curiously, the deformation never turns into caricature. In some cases, the final result, strangely, is quite elegant—on a level, for instance, akin to Van Dongen.

In the later years of his activity, Catelli appeared freer and more imaginative, especially in portraits, painted with audacious use of colour—often exceptional, for a painter like him, for whom exceptionalism was the norm of his painting. Among the works created just before his death, the themes of "readings" stand out, and naturally, the figure of Matildella appears, placed within her surroundings, rendered meticulously in all the episodes that make up the external or internal furnishings—furnishings that carry significant weight in the meaning of the composition.

From 1977, there is La lettura (The Reading), which I consider one of the most complete and brilliant works conceived by Catelli. The girl is seated in a corner of the terrace, against the sun and the view of the Camaldoli. Resting on the balustrade that overlooks the lawn, her legs stand out against the abstract design of the ceramic floor. Here, the work is truly total; the designs intersect and combine organically, creating an exemplary, free form of cubist image, without any academic reference. This painting and others created in the same period, shortly before his death, represent the highest achievements of Catelli—exemplary and unrepeatable works, even in an artist who, throughout his full and vibrant life, made exceptional results his norm.

Thus, this old wise peasant-gentleman from Naples, this man of the nineteenth century who lived isolated on a hill far from the city, surrounded only by his children and grandchildren, this peaceful, kind, tolerant man, patiently created the images of his extraordinary poetic and fantastic world every day, outlining a reality that, I repeat, was harsh but nourished and "alive" in the climate of the most advanced figurative culture of the time, with characteristics and styles that were coherent, original, and well-defined—an art that, in short, fits into history. After all, as a keen reader of De Sanctis, Catelli once wrote in one of his notebooks, where he often confided his thoughts: "The history of art is the history of humanity; it is the story of how man has seen his own time."

From the height of his long life, Camillo Catelli knew how to explore and retrace, one by one, the experiences of modern figurative culture. He is the most authentic expression of an artist who, solely through instinct—a grace and fantasy-illuminated instinct—achieves results that even others, deeply embedded in culture with conviction and full awareness, struggle to affirm. The secret of Camillo Catelli lies in his "innocence," but an "innocence" that is profoundly aware of being a man among men.

(1) This quote, along with others that follow in this text, is taken from the handwritten notebooks of Camillo Catelli, which he kept over the course of several years.